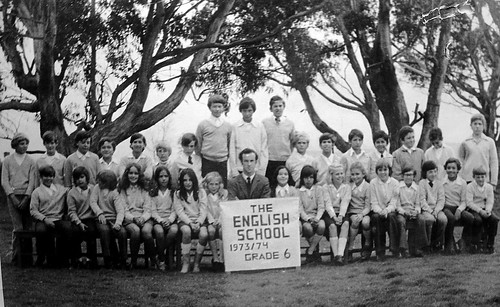

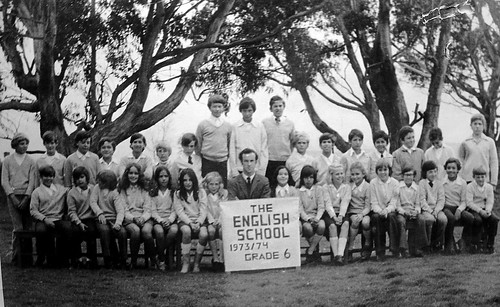

From second grade until I left for Canada in 1974, I went to a school in Bogotá called

The English School. Like most schools in Colombia, public or private, it had a uniform, and I wore a pair of brown pants, brown shoes, and a white shirt under a light brown sweater. Even today, putting on that colour combination makes me sweat.

The school was in the middle of nowhere. Since Bogotá was laid out mostly North-South in those days, distance from civilization was measured in terms of what street you were on. The pastureland began more or less at the

Calle Cien or 100th Street, a street that had been laid out to form a beltway around a city that knew no diet. The school itself was on Calle 177, at the then-distant third bridge over the main road out of Bogotá to the North of the country, the

Autopista del Norte.

We rode buses to get out there - buses of legend, of the old Bogotá, before the government decreed that all buses had to be painted according to the colors of the company they belonged to. Each company had rumours attached to it, and the buses lived up to them. Bus Number One was with the

Flota Macarena, and the bright orange Ford often flashed by us on the Autopista, the cheerful driver flashing an enormous smiling set of teeth at us from under his hedge of a mustache. The Flota Macarena was known for fast driving and poor brakes, but we all desperately wanted to be on Bus Number One, because they always got there first. Even of it was off the edge of a cliff.

I can't fail to mention Bus Number Seven. My bus. A dark blue relic of the 1940's, its enormous vertical radiator was a series of chrome bars perched between two blue, hulking mudguards. A set of beady headlamps were perched on top of the mudguards. I think it was leased from the

Rapido Pensilvania company, but it was far, far from rapid. By the time Bus Number Seven had accelerated enough to get out over the hump at the main gate of the school, Bus Number One had already made it back to the Second Bridge. No matter how much we egged the driver on, he maintained a steady plod homewards, never varying from his spot, steadfastly blocking all traffic by persisting in travel in the fast lane. On those rare days when Bus Number One was delayed, and left after us, they would soon catch up, and usually undertake us on the shoulder, scattering dust, gravel, and occasional unfortunate pedestrians.

Once, during a trip that my parents took to Curaçao or Trinidad, I stayed with my godparents, the Biagis. This meant that I travelled on a different bus to school - I don't think it was Bus Number One, because I remember being on a green

Expreso Bolivariano. The best part was that this bus would stop during its rounds for a fruit hurling fight with another bus. The buses would line up, down would come the windows, and broadsides of apples, oranges, mangoes,

uchuvas and

mamoncillos would be exchanged. I don't even remember whether the other bus belonged to the same school or if it was perhaps part of the American school, the

Nueva Granada, or the German school, the

Andino. What is certain is that the parents of both busloads were proud of their children's fruit consumption, not being aware that it was in fact ending up either on the side of a bus or squashed in the tarmac.

The school itself was in the middle of farmland, and what was left of the millenial Bogotá swamp, the

humedales. I too often fell or was thrown into the

chambas or ditches, got stuck in the deep ooze between the waist high tufts of wild kikuyo grass during cross country runs. I even saw several calves born in the field across from the third grade classrooms. Favorite games in those times were to take enormous

chizas, or beetle larvae, and chase girls around the sandy playground, or to wage organized war with the thousands of eucalyptus acorns that fell from the trees lining the

chambas.

Many years later, I drove on Calle 177 again and stopped at the gate of the English School. I stood and peered through the locked gate. It was an almost completely different place - gone were the blue and white vertically striped prefab huts that served as classrooms, replaced by a large brick and glass multi-storey structure. The school was surrounded by housing developments that reached out to Calle 200 and well beyond. The old house that had served as the administration building was only slightly visible through a whole set of suddenly-grown-up trees.

The only thing that seemed to remain was the front parking lot, full of buses of all different colours, ready to burst forth, full of children, some of whom undoubtedly had saved some fruit from their cafeteria lunches.